A typical noun phrase is composed from a preposition, an optional

quantifier, a noun and an optional string of adjectives. A quantifier

is a special kind of noun that tells us how much of the main noun there

is, such as "one", "a pair of", "some", "none". Prepositions are

also used to express grammatical case. The only inflection on a noun

itself distinguishes whether it's definite or indefinite.

There is no formal difference between a noun and an adjective, so the

word |qar| can mean both "red" and "a red one". From the words |setam|

"guarding, guard" and |warve| "dog" we can make both |warve setam| "watchdog"

and |setam warve| "dog guardian". In general, adjectives are just

nouns that are chiefly used to describe other nouns.

A noun can be indefinite (a tree) or definite (the tree).

In Obrenje, these qualities are expressed as noun inflections. They

are quite regular. Irregular nouns are always marked as such in the

dictionary.

The lexical form of the noun is the indefinite one. In order to make it definite, the stress is shifted further to the end of the word. In most cases, this is done by appending an |-e|. The exceptions are nouns that end on -CCV, that is, two consecutive consonants and a vowel. In that case, the definite form is made by placing the vowel between the consonants: -CVC.

For example, the word *|tok| /tOk/ has the definite form *|toke| /"to:kh/. For the word *|toka| /"to:ka/, the inflected form would be *|tokae| /tO"ka:/. Finally, the word *|tokla| /"to:kla/, which has a -CCV ending, would turn out as *|tokal| /tO"kal/.

Proper names are usually not inflected, since it's assumed that a person, place or thing that has a specific name is always definite. One can use the inflection for rhetoric effects though:

Tase u sinel, moe u sinele.

Lit.: "She's not a Sinel, she is the Sinel."

"It's not just any woman named Sinel, it's the one Sinel I told you

about."

More informations about the use of definiteness can be found in chapter

3.3.

Quantifiers and Pronouns.

In Obrenje, prepositions are not only used for the "classical" prepositional

duties, but sometimes also for the roles played by cases in other languages.

The difference between cases and other prepositions is that personal pronouns

inflect for case, but not for other prepositions.

The three cases of Obrenje fit neither of the classical systems (e.g.

Nominative/Accusative/Dative, Absolutive/Ergative/Oblique etc...) well;

therefore the following unconventional names have been coined for them.

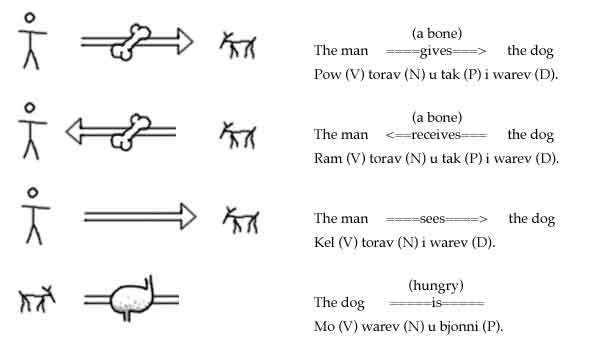

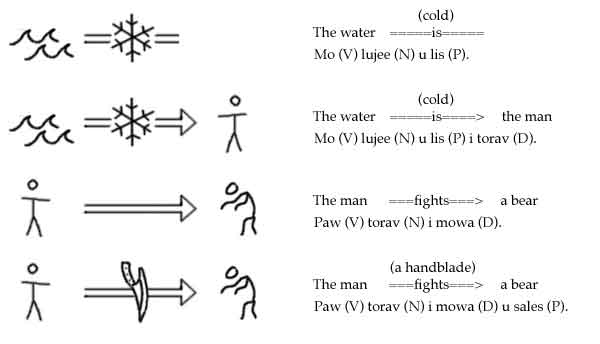

Here are a few sample sentences that exemplify the above structure.

Obviously, the classical accusative-dative system can't be mapped onto these cases directly. The directive case would be translated as accusative in "The man (N) sees the dog (O)", but as a dative in "The man (N) gives a bone (P) to the dog (O)". Similarly, the predicative case corresponds to the classical accusative in "The man (N) gives a bone (P) to the dog (O)" as well as the nominative in "The dog (N) is hungry (P)".

In fact, an object may take either case with a given verb, depending on its role in the verb action:

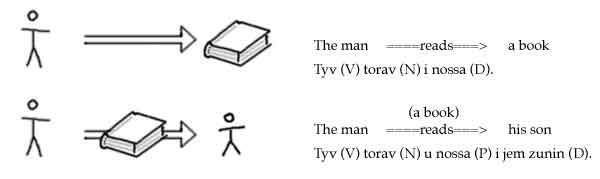

Sometimes, two objects are used in conjunction with a verb that usually takes only one object. In these cases, the predicative is by default interpreted with an instrumental meaning, and the directive with a dative meaning:

Examples for other prepositions:

|ur| descriptive genitive, |kosh| possessive "of", |gy| instrumental "with", |laq| comitative "with", |ki| "to", |kej| "towards, in the direction of", |ro| "in, on, at", |roj| "through", |pri| "from, out of", |prej| "from the direction of", |culle| "within, inside of", |bla| "for, for the sake of, for the benefit of", |tetre| "because of, due to".

|Sine ur pelve| = "the land of wind", |Sine kosh voron| "the land of

the duke", |feggam gy krat| "walking with a stick", |feggam laq voron|

"walking with the duke", |pelve prej soxal| "wind coming from north", |tetre

sil| "due to rain".

Quantifiers are nouns that describe quantity. There are quantifiers

to express singular and plural -- a distinction never made neither in verb

nor noun inflections. They are not mandatory, though, and indeed,

they are rarely used if the quantity is not relevant and ambiguous.

Some quantifiers have an irregular definite form.

Examples for quantifiers (irregular definite form after the comma):

Important: Since quantifiers are nouns, they can be inflected after definiteness. Placing the definiteness on the quantifier rather than the main noun, or on both, can alter the meaning: |kil ombe| "a glass of wine", |kil ombee| "a glass of the wine", |kile ombe| "the glass of wine", |kile ombee| "the glass of the wine". Note that |ombee| is an irregular definite form; the regular form would be *|omeb|.

Important: Quantifier are nouns with a concrete meaning, such as |naja| "society, team", |cenje| "alone", or the numbers, can also be used as regular adjectives after the noun. A number used as an adjective has the meaning of an ordinal: |ce torva| "one man", |cej torva| "the one man", |ce torav| "one of the men" ("one of the man" would make little sense), |torav cej| "the first man" (lit.: "the man one").

Here is a chart of the personal pronouns in Obrenje. They have

the unique property of having a case preposition built in. The directive

pronouns have a special clitic form (given in parentheses) for use

before the verb. The third person pronouns differentiate between

sentient (3s) and non-sentient (3n) nouns. This distinction is not

to be confounded with the implicit-explicit distinction of third person

verb inflections.

| Nominative | Directive | Predicative | Possessive | |

| Person | ||||

| 0 | acae | acaj (che) | acaw | acam |

| 1 | zae | ez (ze) | zaw | xim |

| 2 | lee | il (le) | lew | lem |

| 3s | jae | je (je) | aw | jem |

| 3u | ae | e (e) | e | em |

| relative | ba | bi (bi) | baw | bem |

| reflexive | nos | ne (ne) | nu | nim |

The nominative pronouns are rarely used, since they don't convey any more information that the verb ending already does. The other pronouns act as nouns, and can be modified by quantifiers and adjectives just like other nouns. However, if a quantifyer comes before the pronoun, the case preposition needs to be stated again.

Possessive pronouns are preferably placed before the noun phrase, since they help to establish the context. They can be seen as quantifiers: |Xim lawne| "My song(s)", lit: "mine of the songs".

After prepositions other than |i| and |u|, the directive forms of the personal pronouns are used.

|Ulaze il.| "I love you." |Ulaze i na il.| "I love you all." |Ulaze i cene il.| "I love only you."

(Note that in the last sentence, |cene| is definite. With the indefinite form, it would be: |Ulaze i cenje il.| "I love only one of you." -- a wholly different meaning.)

When using quantifiers together with personal pronouns, it is often

preferable to place the quantifier after the pronoun. For example,

if one wanted to say "I see y'all", the regular quantifier structure would

be |Kelze i sej il|, literally "I see the several of you". Using

the quantifier |se| as a regular adjective, however, yields |Kelze il se|,

"I see the multiple you" -- a more succinct expression with the same content.

© 2001 by Christian Thalmann

cinga (at) iname (dot) com